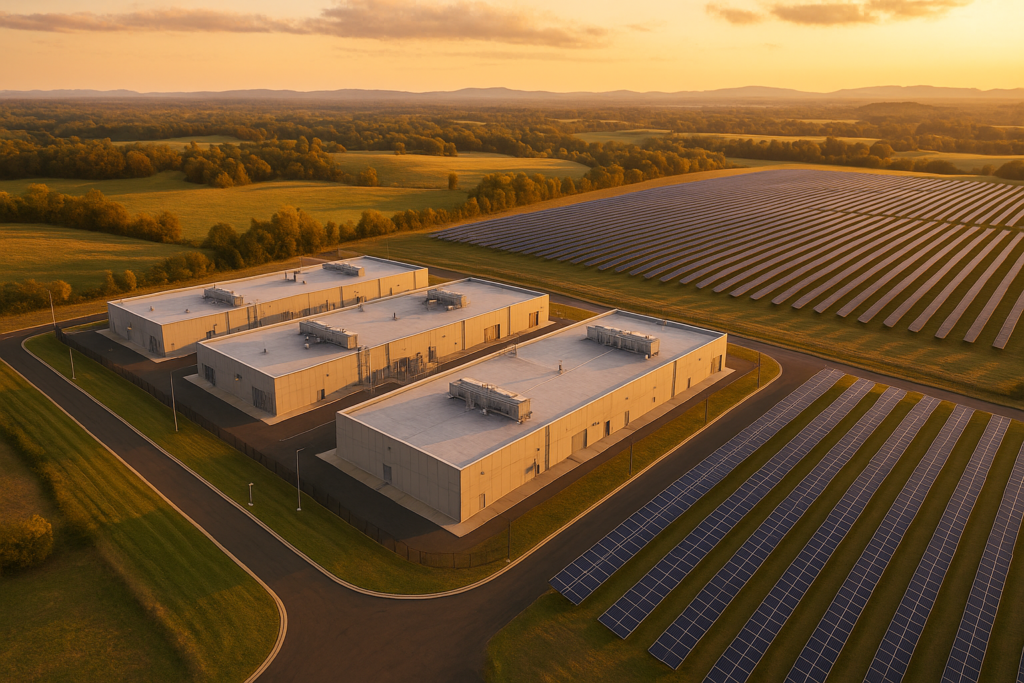

American Energy, American AI: Powering a Secure Future

Key Takeaways Artificial intelligence (AI) and data centers are driving unprecedented energy demand growth, shifting industry conversations from megawatts to gigawatts. Permitting reform and policy consistency are critical to maintaining […]